On Friday, March 28th, near Missoula, the Clark Fork and Blackfoot Rivers flowed freely past the remnants of the Milltown Dam for the first time in over a century. The earthen dam above the flat ground where the dam powerhouse once stood was breached near high noon, and the water wasted no time in following the path of least resistance through a shallow channel into the powerhouse flats and on down the Clark Fork River, where it undoubtedly continued flowing through northwestern Montana, into Idaho, pausing for a time at lake Pend Oreille, then finally moving on to the Columbia and the Pacific Ocean. While the breach has garnered considerable media attention, the real story is not the breach itself, but the history and context that led a community to spend an ocean of time and money to unmake what our history made.

Hundreds of people turned out to witness the breach on a chilly spring day, braving the icy slopes of a steep bluff to catch a glimpse of water in motion. To understand the significance of the dam breach, and why the crowd came, requires some knowledge of the history of the dam and the Clark Fork River. This story has been sadly overlooked in most media coverage, and without it, the dam breach could seem like a dog-and-pony show. "What’s the big deal?" the uninitiated might ask.

The big deal is mining, and copper, and electricity. Today, more than a century removed from the dark old days of pre-electrification, it is easy for us to take the power lighting our homes and revving up our armies of gadgetry for granted. But our brave new world came with a staggering cost, and the Milltown Dam and the Clark Fork River were a part of it.

As demand for copper soared in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, due significantly to its use in the transmission of electricity and also in war-related applications, 120 miles upstream from Milltown, the city of Butte was bustling. Men risked their lives for the prospect of a good paycheck to pull as much copper out of the ground as was humanly possible. The underground tunnels required lots of timber supports, and the process of extracting copper from raw ore through heap roasting and, later, smelting and concentrating also demanded wood to fuel the fires. As a result, William Clark, one of the three legendary Copper Kings, the mining barons of Butte, built a mill at the confluence of the Blackfoot and Clark Fork Rivers. Milltown was born.

To power the mill and to produce electricity for his utility that served the cities of Milltown and Missoula with an electric streetcar system, Clark built a dam along with it, the same dam that is generating so much interest these days. The dam was barely finished when a 1908 flood of epic proportions, some call it a 100-year flood, some say a 500-year flood, struck the Clark Fork River.

To understand what happened next, we need to understand the situation upstream in Butte and Anaconda in 1908. Mining and smelting had been going full-tilt for decades. While the ore mined in Butte at the time was high-grade, sometimes approaching 30% copper, the mines still generated huge amounts of waste. The most prominent form of mine waste was tailings, the fine-grained, sand-like sediment that is a byproduct of the milling and concentrating process. Rich in sulfides, heavy metals and arsenic, when mixed with water and oxygen tailings render sulfuric acid, which further mobilizes metals and arsenic into solution at toxic levels, through a chemical process known as acid mine drainage. At the time, these tailings were simply discharged into the nearest convenient creek. Acid mine drainage was not a concern- maximizing copper production was. In Butte, Silver Bow Creek turned into an industrial sewer, with tailings spread out over the floodplain. In Anaconda, tailings from similar operations were dumped into Warm Springs Creek and also spread throughout the southern end of the Deer Lodge Valley. Both creeks sit at the headwaters of the Clark Fork River.

The 1908 flood picked up a massive amount of tailings and other mining wastes and washed it down the Clark Fork. Throughout the Deer Lodge Valley, some tailings settled in the floodplain, resulting in small patches of dead soil called "slickens" where vegetation is unable to grow. Past the town of Deer Lodge, the Clark Fork’s channel narrows as it enters a series of canyons running northwest to Missoula. The narrow channel means faster water, so less tailings waste settled out in these stretches than in the wide-open Deer Lodge Valley. Instead, these tailings were swept up in the swift current until they backed up against the Milltown Dam. About 8 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment were deposited behind the dam. The structure itself was almost washed away in the flood, and Clark had to send miners from Butte, well versed in explosives, to dynamite out the spillway so that the whole thing, powerhouse and all, would not be washed away.

And those tailings have remained at the dam until the past year. The current dam removal and restoration project, carried out beneath the umbrella of numerous federal and state agencies under the banner of the Superfund law and implemented by Envirocon, a private company, is removing the most toxic of that sediment. Every day since last October, trainloads of the stuff have been making the trip to their new home back upstream just outside of Anaconda near Opportunity, where they are unloaded and spread out over the top of the 160 million or so cubic yards of tailings that are already there, a legacy of the big old smelter stack that still stands over Anaconda, casting a long shadow that stretches out to every light switch and electrical socket in the country.

The good news is that the contaminated sediment being shipped from Milltown to Opportunity is considerably less nasty than the stuff that is already there. Because the tailings deposited at Milltown have been underwater in the Clark Fork River for a century, organic matter and other sediments carried by the river were mixed in, rendering the Milltown tailings sediments richer and with a lower acidity and concentration of metals. The state and federal cleanup crews' hope for Opportunity is that the Milltown sediments will serve as a cap, allowing vegetation to grow over the top of the Opportunity tailings, providing a barrier to infiltration into area groundwater and a cap to minimize blowing dust problems.

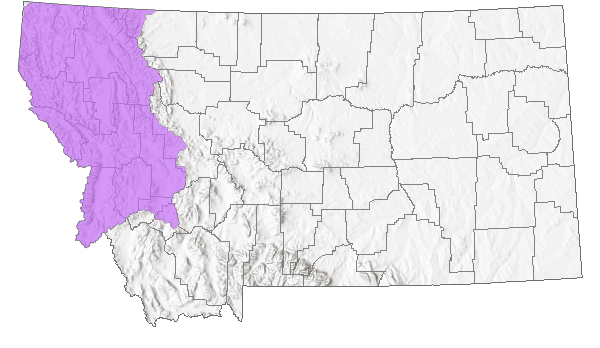

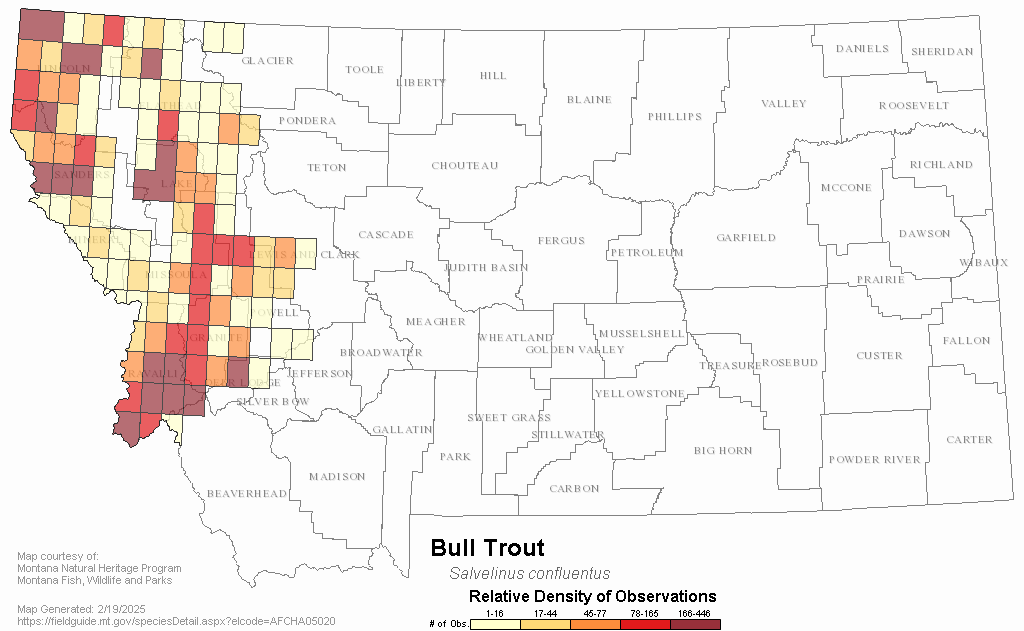

The motives for the dam removal are directly tied to the tailings deposited at its base. In 1981, arsenic was found in Milltown groundwater. It had infiltrated from the tailings deposit, and posed a human health risk via residents wells used for drinking water. The dam also was problematic for fish, particularly bull trout, listed as a federally threatened species in 1998, as it blocked significant migratory routes from the Lower to Upper Clark Fork, and the reservoir behind the dam created prime habitat for non-native, predatory pike. There were also concerns that the dam was old and decaying, fears that were magnified by an ice jam event near the dam in the mid 1990’s. Compounded, these reasons added up to the ongoing dam removal.

And last month’s breach was only a part of the overall restoration of not only the dam site, but the entire Clark Fork Basin. Upstream, the restoration of Silver Bow Creek continues. The Opportunity site, formerly known as the ponds, now affectionately referred to as the BP-Arco Waste Repository, looms, and we are left to watch and wait and hope that sprouts will appear in the new layer of Milltown sediment. Across I-90 from Opportunity, the Warm Springs Ponds, where lime is added to the waters of Silver Bow Creek to reduce its acidity and cause heavy metals to drop out, remain a question mark. In the short term, the ponds have become excellent waterfowl habitat, but the future of that site, like so much of the Clark Fork, is unclear.

In other words, restoration is not a one-day celebration. The dam breach, while certainly a pivotal moment in the history of the basin, is only a small step toward a healthy river system, toward undoing the damages a century of careless progress wrought. We are all culpable for those damages, so long as we continue to enjoy electricity, and we all share part of the moral obligation to preserve and restore this high wild river basin. And, make no mistake about it, restoration is no simple matter. It will take money and hard work to return the Clark Fork to a healthy ecosystem, and, more than anything, it will take time.

The crowd that came out for the dam breach greeted the free-flowing waters of the Clark Fork and the Blackfoot with cheers and rapt attention. It was inspirational to see so many so invested in the restoration. If the restoration of the Clark Fork, America’s largest Superfund site, is to succeed, then we must maintain our focus and our respect for these wild places, and make those values a foundation of our Montana culture. The dam breach is a good start. We should take strength from it. There is still much work to be done.

Above: A restored reach of Silver Bow Creek near Butte shows a developing riparian plant community.

Above: A restored reach of Silver Bow Creek near Butte shows a developing riparian plant community. Above: An unrestored reach of Silver Bow Creek near Anaconda has little vegetation along the streambank due to the presence of mine tailings; these acid and heavy metal-laden soils prevent most plants from growing. This reach is slated for restoration in the next 1-2 years.

Above: An unrestored reach of Silver Bow Creek near Anaconda has little vegetation along the streambank due to the presence of mine tailings; these acid and heavy metal-laden soils prevent most plants from growing. This reach is slated for restoration in the next 1-2 years. The site, formerly the Opportunity Ponds, was a tailings repository for the Anaconda Smelter. It covers an area of over five square miles, with deposits of mine waste averaging about 20 feet deep. Due to that considerable volume of contamination, wastes removed from elsewhere in the Clark Fork Basin are transported to the Opportunity Ponds site. Topsoils are then revegetated to reduce erosion.

The site, formerly the Opportunity Ponds, was a tailings repository for the Anaconda Smelter. It covers an area of over five square miles, with deposits of mine waste averaging about 20 feet deep. Due to that considerable volume of contamination, wastes removed from elsewhere in the Clark Fork Basin are transported to the Opportunity Ponds site. Topsoils are then revegetated to reduce erosion.